When Action Speaks Louder than Words: How VR task design reveals new sides of collaboration

October 7th, 2025

Dennis Osei Tutu

Communication is never just about what we say. It unfolds in the glance we share with a partner, the gesture that directs attention, the pause that signals it’s someone else’s turn to speak. These subtle rhythms form the choreography of human interaction - yet they are notoriously difficult to capture. Traditional role-play exercises can surface fragments of this dance, but much is lost in the process: the fleeting eyebrow raise, the spontaneous pointing gesture, or the micro-pause that carries meaning in silence.

Exploring Communication and Collaboration Through VR

Virtual reality (VR) offers us a new way forward. Unlike classroom exercises or controlled lab studies, VR allows people to immerse themselves in shared, interactive scenarios while sensors quietly record their gaze, gestures, facial expressions, and speech in fine detail. Movements that no human observer could consistently track are logged with precision. This creates a unique opportunity: to explore not only what people do in collaborative settings, but also how the design of VR scenarios themselves can shape — and ultimately teach us how to design for — different modes of collaboration.

In our latest study, we set out to test exactly this. Could two carefully structured VR tasks - one encouraging free-flowing interaction, the other enforcing deliberate structured exchanges - reveal different sides of communication and collaboration?

Two Tasks, Two Worlds of Interaction

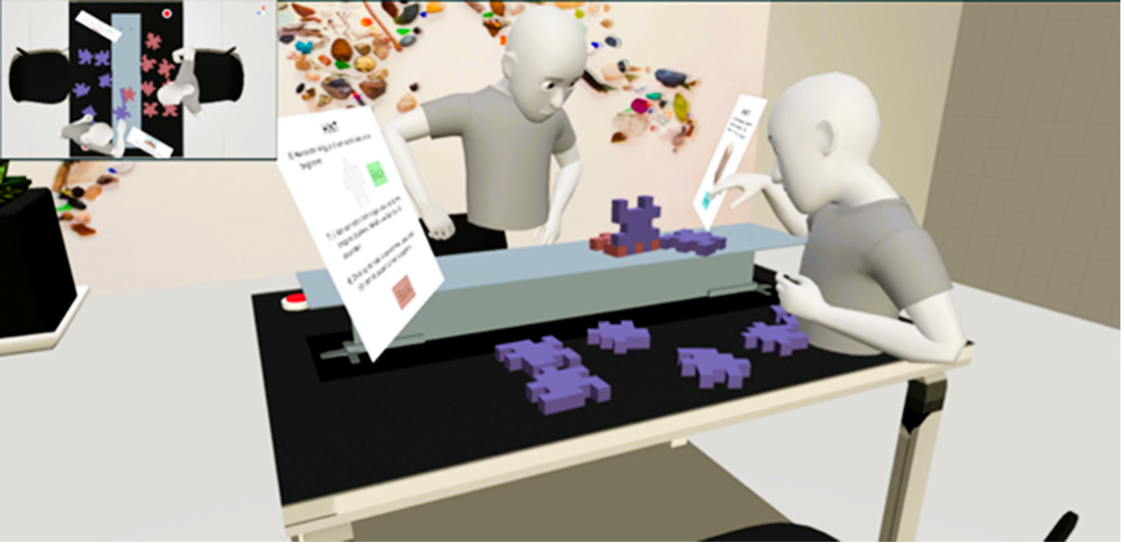

To explore how design shapes collaboration, we asked 24 pairs of participants to take on two puzzle challenges in VR. Both tasks were capped at sixteen minutes and framed as joint efforts: finish as quickly and accurately as possible, relying only on each other. Yet beneath these shared rules, the setups could not have been more different.

In the first task, Dynamic, Known Goal, partners worked together to assemble a cube from interlocking pieces. All materials were visible from the start, and both players had partial sets that only fit together when combined. Progress was marked by the snapping of correct pieces into place, making the activity fast-paced and improvisational. Partners pointed, gestured, and built in parallel, coordinating through quick exchanges and spontaneous cues.

The second task, Structured, Unknown Goal, demanded a very different rhythm. Here, partners sat across a divider that completely blocked the view of each other’s workspace. Instead of a shared structure, they had to construct two identical flat designs in alternating turns, each describing their moves so the other could replicate them. Success depended not on gestures but on clear, deliberate language, with communication slowing into extended turns of instruction and confirmation.

How Did Design Reshape Emerging Virtual Behavior?

The contrast between the two tasks was striking. In the shared-visual task, participants relied heavily on their bodies, using pointing, gesturing, and facial expressions to negotiate the puzzle together. By contrast, when visual access was blocked, gestures gave way to language. Turns of speech became longer, more deliberate, and more carefully structured as partners relied on words alone to align their actions.

One of the most surprising findings came from how partners created shared focus. Without a visible common workspace, they worked harder to achieve joint attention - using verbal descriptions to actively build moments of “looking at the same thing,” even when that object could not be seen.

Taken together, these results show how collaboration adapts to the rules of the environment. VR task design doesn’t just constrain interaction; it actively channels it into different modes — spontaneous gestural coordination in one case, carefully structured verbal negotiation in the other.

Why Does This Matter?

Our findings show that collaboration in VR is not a fixed reflection of individual ability - it adapts to the rules set by the environment. By carefully embedding constraints and affordances, VR tasks can draw out different sides of teamwork: spontaneous gestures in one setting, deliberate verbal negotiation in another.

This has important implications. It means VR is not only a tool to observe collaboration, but also a medium to design for it. Educators can shape scenarios that encourage specific soft skills, trainers can test how teams adapt under different pressures, and future human–AI systems can be built on a deeper understanding of how people coordinate across multiple channels of communication.

In short, VR gives us more than data: it gives us design leverage. How we craft the stage determines the kind of collaboration that emerges.

This post highlights just a glimpse of our findings - the full paper explores the data and design choices in depth.